How Do You Run a Shop in a Neighborhood with No Cash?

March 19, 2009

I’ve always been curious about what happens when microfinance clients open businesses in places where there is very little capital. Many operate small shops of household necessities but the placement of such stores is generally based more on proximity to home than a strategic evaluation of which part of town is most profitable. So how do they cope if their customers can’t afford to buy anything? Last week, I got my answer: credit.

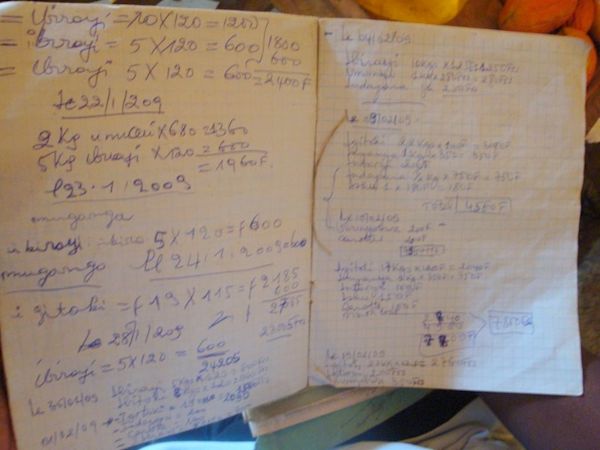

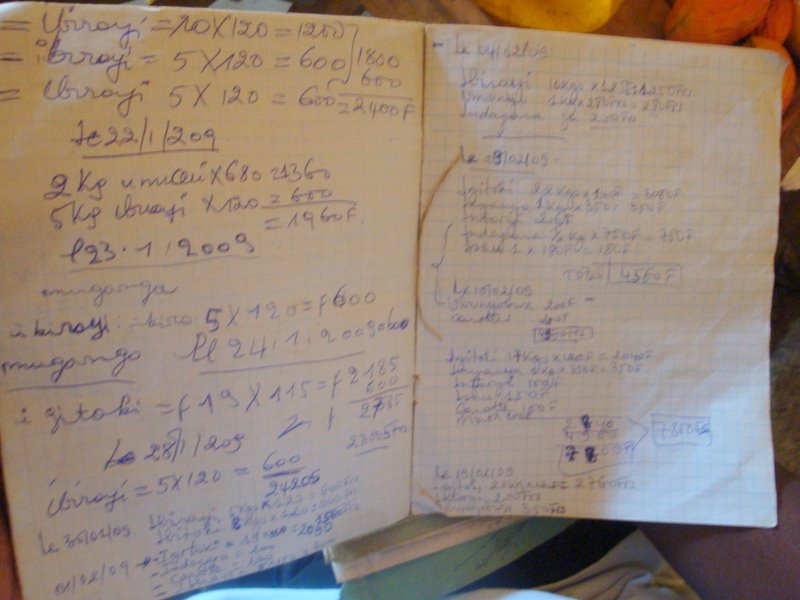

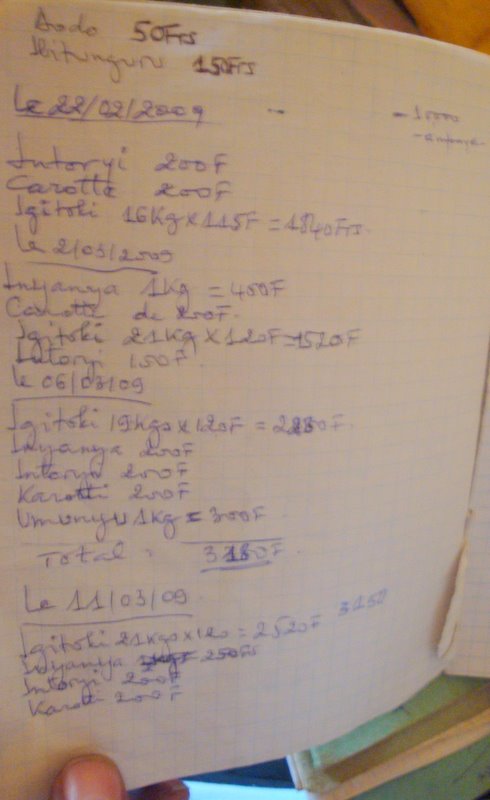

Pen and Paper: How to issue credit, the old fashioned way

I was in the field with the Kiva Coordinator, John, collecting journals. We were meeting with a client who sells vegetables in a small neighborhood in Kigali, Rwanda. After a series of preliminary questions, I asked the client if he was having any difficulties with his business.

“Creditors,” was the translation I received for his answer.

I paused, trying to re-translate it into something that would make sense. I couldn’t quite guess what he meant, so I just asked. Without going back to the client for more of an explanation, John expanded upon the client’s assertion,

“His customers owe him money but they’re not paying.”

Ahh so he may mean “debtors,” in which case this microfinance client is both a credit-receiver and a credit-giver. Could it be? People always speak about Africa’s cash only economy and I have yet to meet a Rwandese with a credit card so it hadn’t occurred to me that there was a widespread grassroots credit system sans plastic. I shared my surprise with the Kiva Coordinator who gave me the dreaded answer:

“You didn’t know that! Everyone knows that!”

“No one ever told me!” I exclaimed in my defense.

“That’s because it’s so obvious!” John countered. Touché.

Apparently, small shopkeepers all over Rwanda accept credit in the form of an IOU from their customers. If I was going to be the last to know (did all of you already know this?) I wanted to at least fully understand it, so I dove in. What John and the client explained is that most of his customers are regulars. They live nearby and he knows them well. A lot of them don’t have cash in the middle of the month but they still need vegetables so he keeps a record of what they have purchased and at the end of the month he presents them with their tab. He keeps careful records to know exactly how much each customer owes him. When I asked to see the records, he produced three notebooks with pages and pages filled with customers’ bills.

Here, one page of his careful notes of what his customers owe

Lately, he says people aren’t paying. Unfortunately, he doesn’t feel that he can stop accepting credit. If he did, “he wouldn’t sell anything,” John explained. But how does he ensure repayment? How can he get the money if his neighbors insist there is none? He didn’t seem to have an answer. The difficulty with grassroots credit, I suppose, is that there are not systems to ensure that the creditor is ever paid. He could refuse to sell to his customers until they pay, but then they could go to another vendor. He could employ some sort of social pressure since he is based in a small community and try to make it a social taboo not to pay, but if many people in the community are in the same position, that won’t necessarily work.

I don’t have a good solution as to how to get the client his money. We all talk a fair amount about the principle of credit and debt. We debate whether it is wise to purchase things if you don’t have the money to do so. As a shopper myself, I have attempted not to purchase goods on credit unless I knew I would have the money to pay for them at the end of the month. So are this client’s customers wrong to buy vegetables when they’re not sure if they can afford it? If he stopped accepting credit, sales would decrease because clients couldn’t afford the goods or because there would only be a few days each month that they could. The credit keeps his sales more constant which from a stocking perspective is wise in a perishable goods market. But if his customers are buying without knowing if or when they can pay, then credit isn’t being used properly. For me, a large credit card company would be the victim and they would ultimately sock it to me through large fees. Unfortunately, this client doesn’t have that kind of leverage. So what’s the solution? Is there a scenario in which he can keep his business profitable in a neighborhood where customers can’t pay?

If you’d like to see all of Vision Finance Company’s currently fundraising loans, click here. To join Kiva’s Vision Finance Company lending team and to support Kiva’s Rwandese entrepreneurs, click here.

Julie Ross is currently serving as a Kiva Fellow at Vision Finance Company in Rwanda. In December she completed her first placement with BRAC Tanzania.

/>PREVIOUS ARTICLE

Kiva IT Internship Program →NEXT ARTICLE

Kiva Sponsors "Microfinance, CA," microfinance conference in Palo Alto, CA →